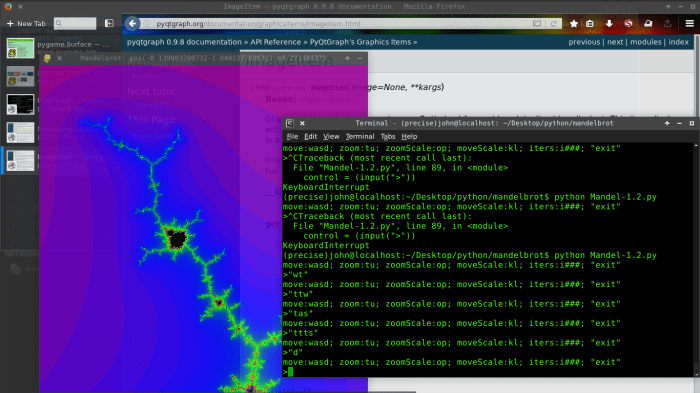

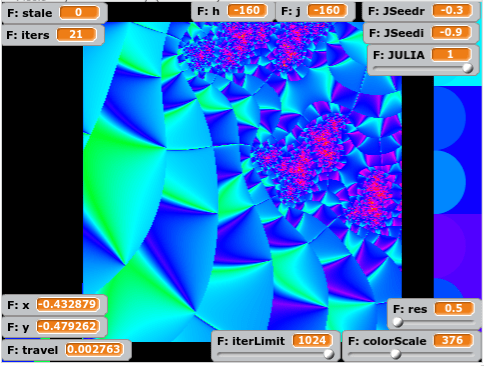

Over spring break, I decided I still wanted a better understanding of how points in the Mandelbrot set moved. I also wanted a more flexible fractal generator than my current one.

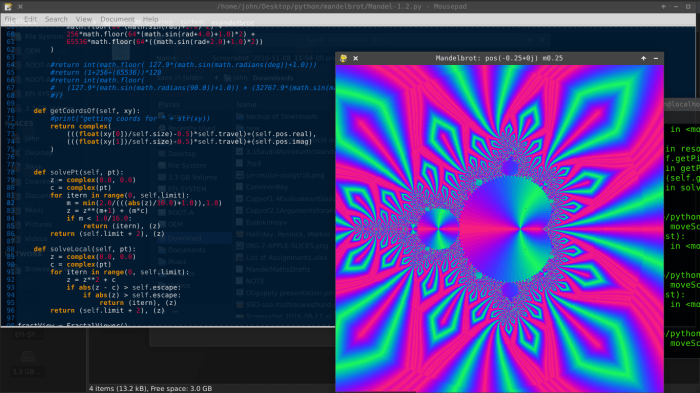

So I stripped my ‘Mandelphone’ project down to nearly nothing, and rebuilt it into yet another program that can’t be moved back to my phone because it includes Pygame. I hope to clean up my code and post it here soon.

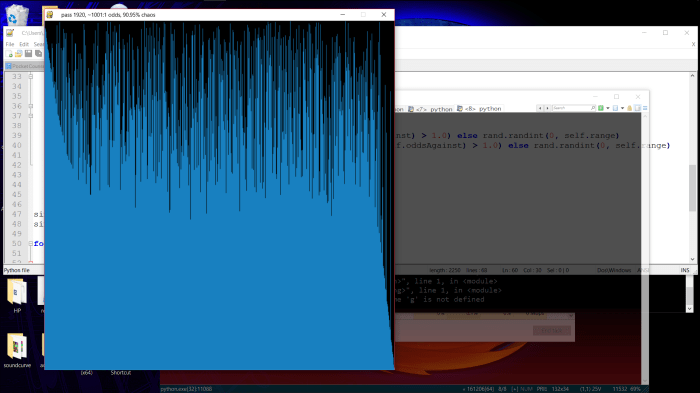

one of my first experiments was to generate the Buddhabrot; Not to answer my real questions, but as a topic for my code – a way to work out a good design. I settled on a large class FractalPanel with several global parallel arrays, and switches to enable/disable certain actions on them.

My explanation (excuse) for using many parallel arrays is that I thought it was faster. After asking about python’s performance in such situations on Quora, I got a clear and concise answer from Simon Lundberg: pointer dereferencing overhead is negligible, because nothing in python is ever in the cache. The next thing I do will be to refactor everything.

But many things will stay the same. The two most important arrays are bucket[][] and raster[][].

Bucket[][] stores the complex starting positions for every pixel in the screen. By storing them in an array, I can easily update them (e.g. to iterate them all and show where every point is after n iterations, then n+1, then n+2, whatever.)

Any methods I have for drawing an image write their results to raster[][] which is copied to a pygame.Surface and drawn at the end of a frame. I have separate methods to rasterize a Buddhabrot from the starting coordinates in bucket[][], or to rasterize the coordinates in bucket[][] itself in various ways.

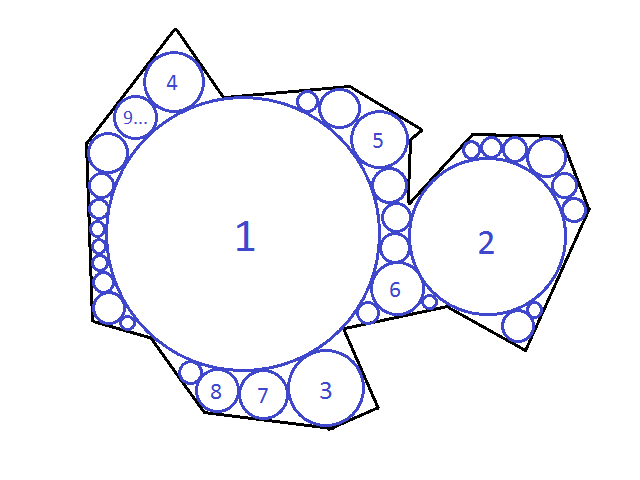

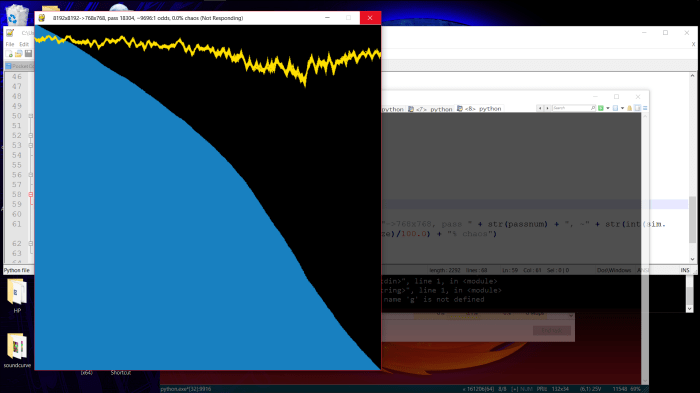

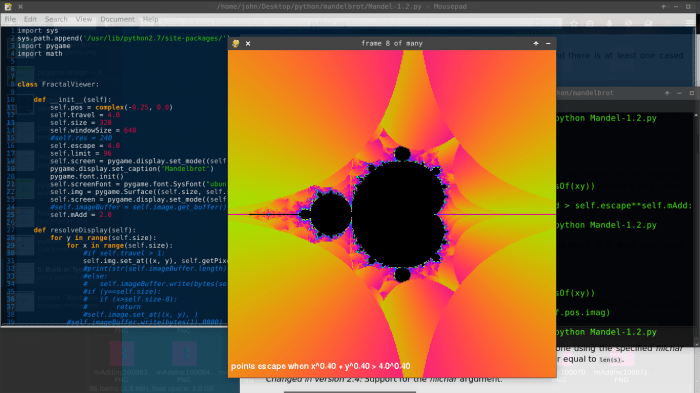

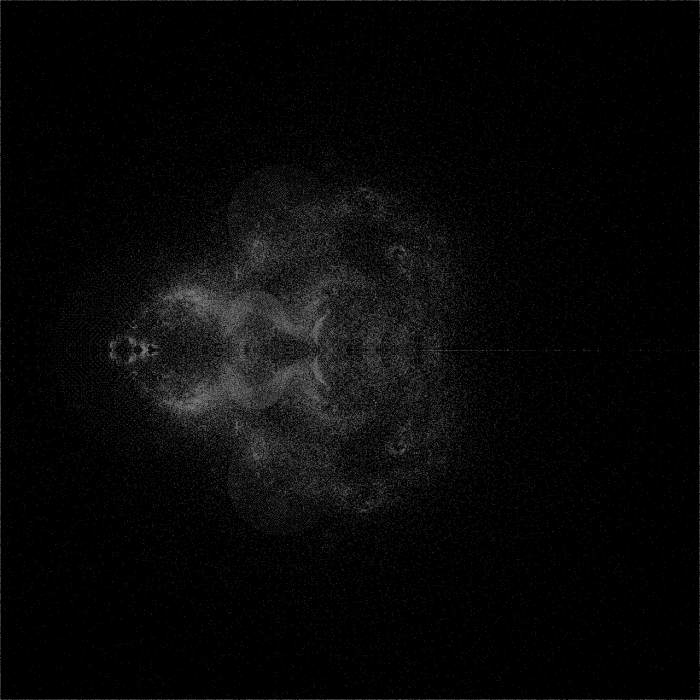

I started by creating a simple Buddhabrot:

These images of the Buddhabrot represent all pixels visited by every Z which started at a coordinate in the bucket. To get more starting points for a more detailed image, I simply iterated the points in the bucket, to get new buckets. (While the images show only the motion of unbounded points, the bucket of starting positions contained both bounded and unbounded points. And YES, as they travel, many bounded points regularly visit coordinates that aren’t bounded when used as starting positions.)

Near the end of the sequence of images, the Buddhabrot is much dimmer, as many unbounded points in the bucket have escaped and aren’t being used as starting points anymore:

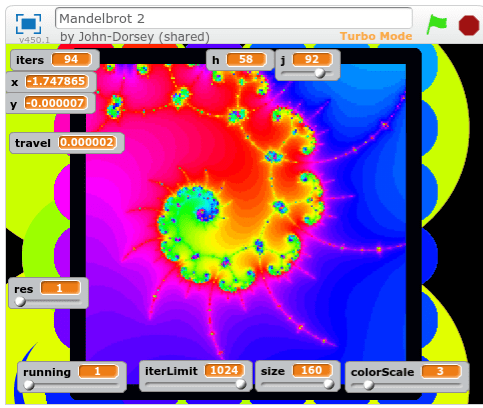

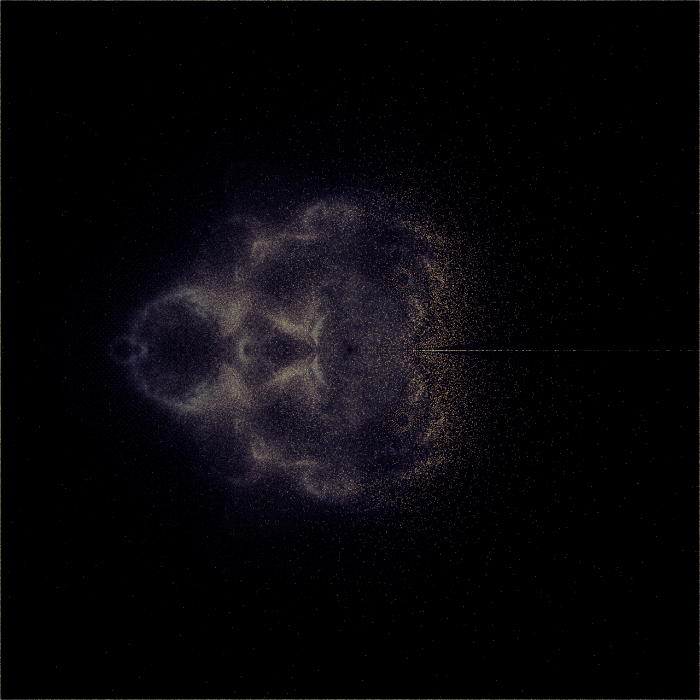

Finally, I combined my 430-frame PNG sequence into a single image:

Coloration:

- red = percentage of the time a pixel is ever occupied.

- green = root-mean-square of pixel brightness, multiplied by 2.5

- blue = mean of pixel brightness, multiplied by 1.5

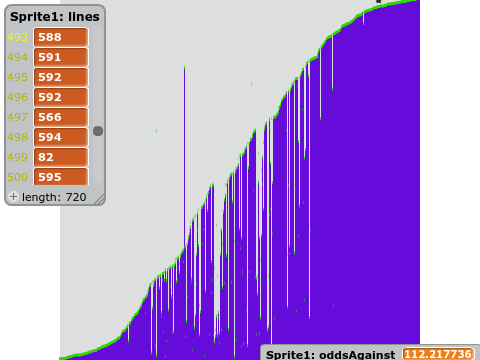

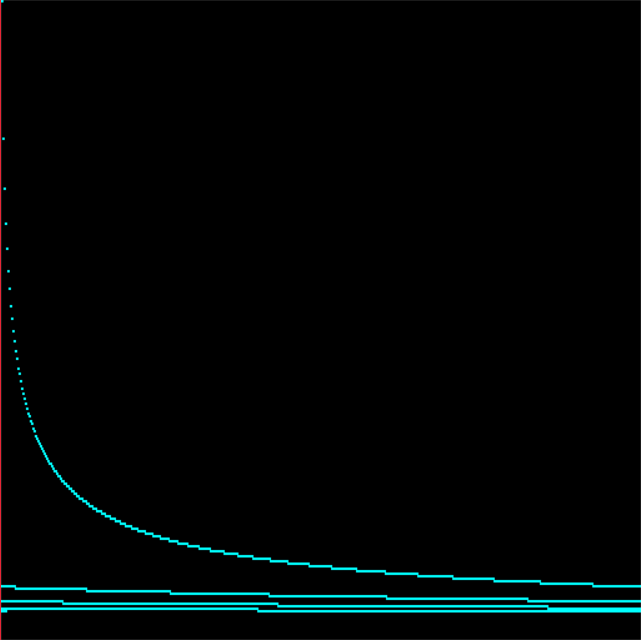

The original images were colored using an Arctangent normalized to 255. Here’s the relation between times visited and luminosity:

I regret how much information is lost by the steep increase in output brightness for single-digit inputs, but my goal was for such points to be visible to the naked eye, with no need to brighten the image in Photoshop. And there’s little need to extract actual numbers from these images, as it would be faster to just regenerate them.

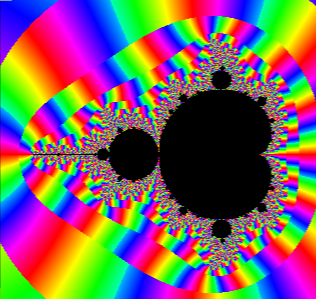

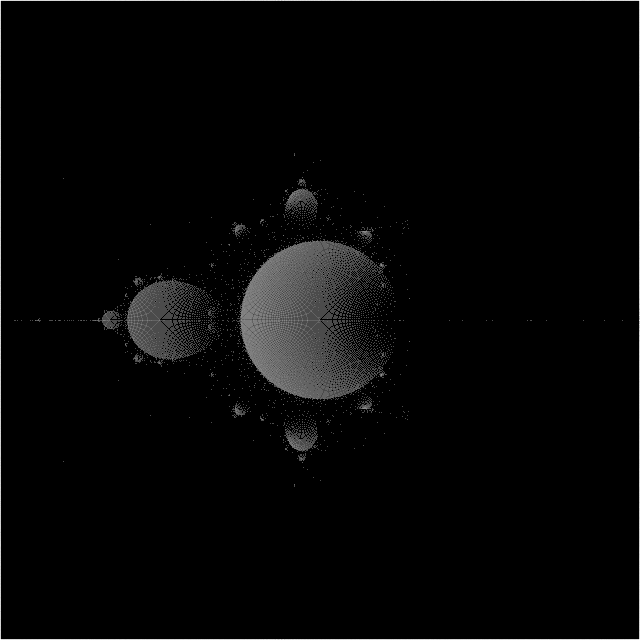

Using points visited by bounded paths as the starting points for unbounded ones gave me some interesting patterns that I’ve never seen before, which I might continue to investigate. but honestly, I’ve always felt that the Buddhabrot was like looking for shapes in the clouds – it doesn’t provide much insight into how points are actually moving. The Anti-Buddhabrot accomplishes this better, I feel, because it helps you see the periodicity of densely traveled paths. (the Anti-Buddhabrot consists of the pixels visited by all bounded points)

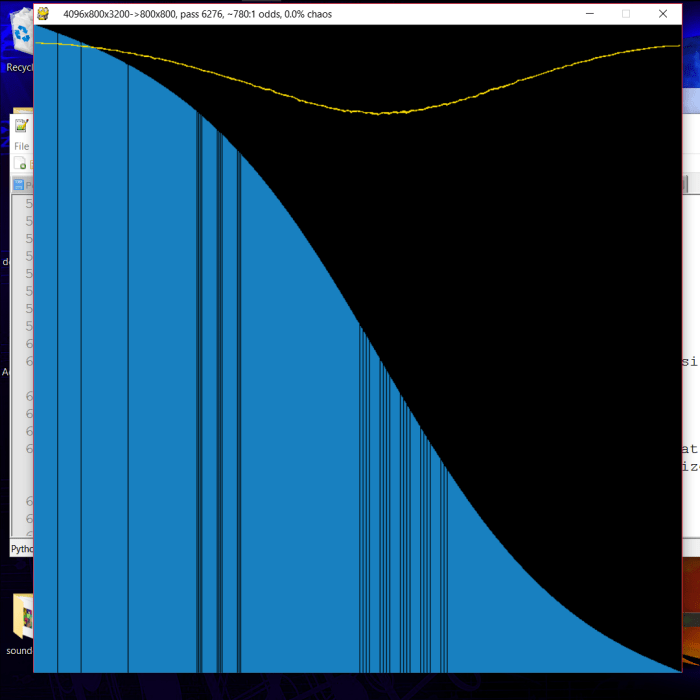

The left bulb, with a periodicity of 2, moved can be seen moving in and out of the cardioid in a simple 1 – 2 – 1 – 2 fashion. The top and bottom bulbs, however, are moving in a triangle. 1 – 2 – 3 – 1.

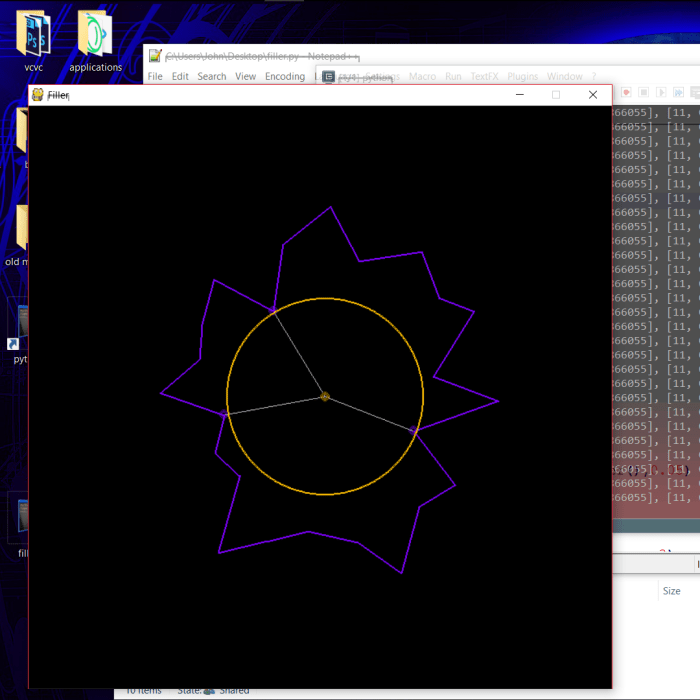

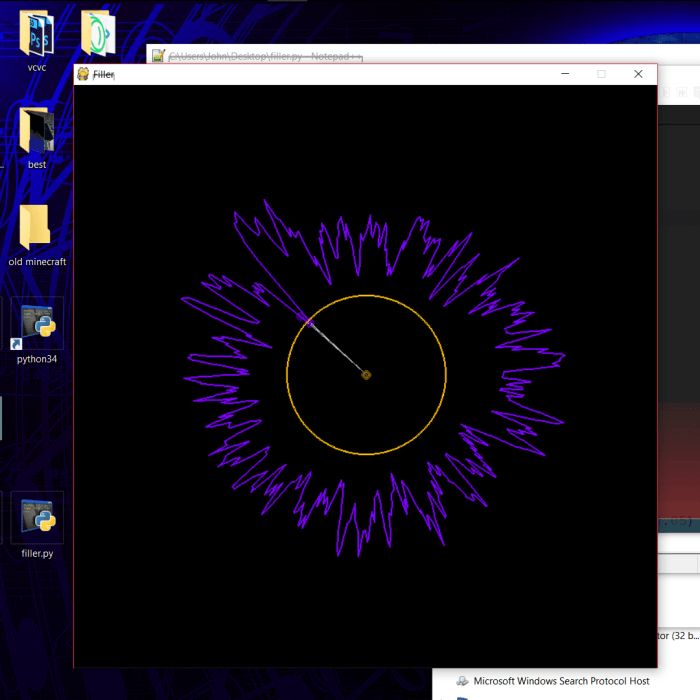

I wanted to see more of this, which led me to my next experiment.

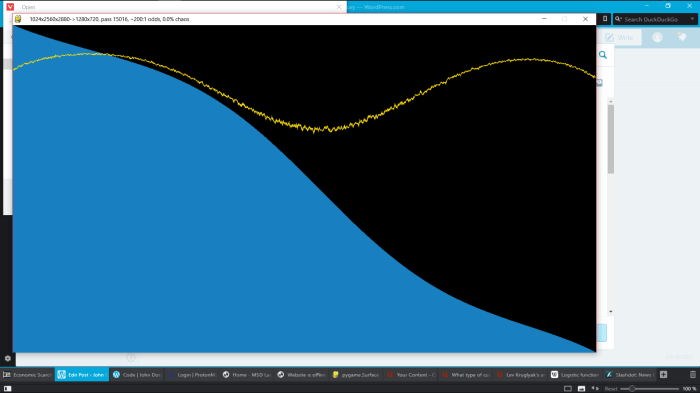

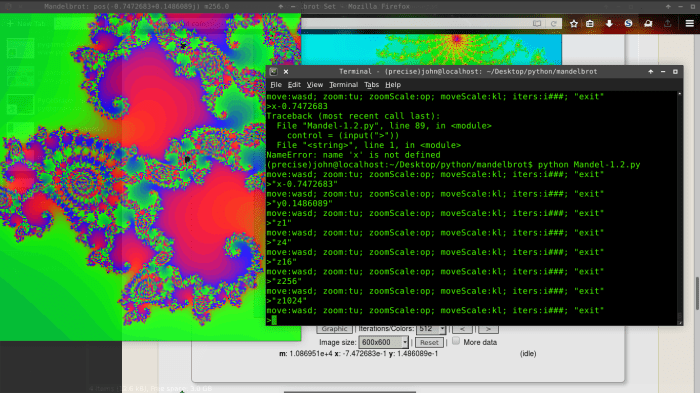

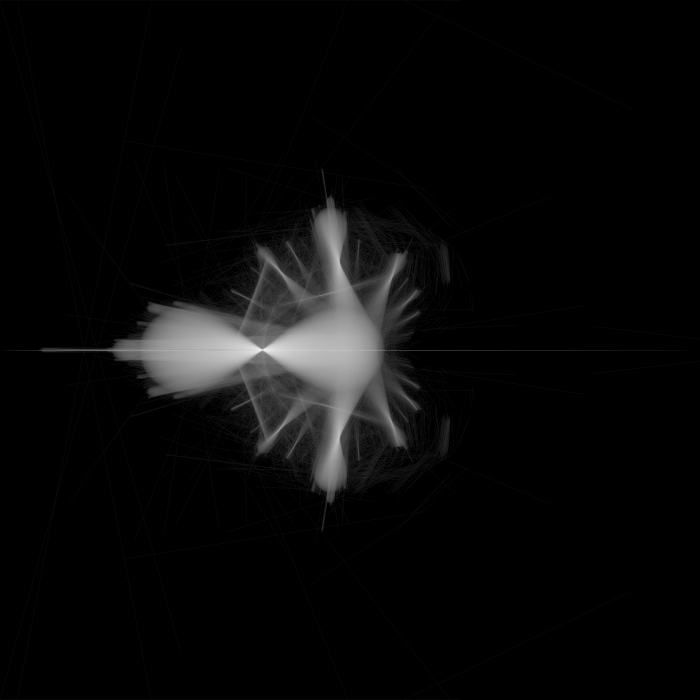

Drawing lines instead of points.

The above image is simply the paths taken by all points as they transform from this:

…to this:

In fact, in the image of all points at 358 iterations, two bulbs can be seen that haven’t coincided with all the others. Their movement during the 259th iteration forms the two lines that are perpendicular to the spokes of the linear movement image, near the left of the cardioid.