Hey!

Conway’s Game of Life is one of the coolest interactive examples of the beauty of mathematics. But realize that it’s only interactive because a huge community of people have chosen to interact with it – to build tools to toggle cells in a grid while operation is paused, then unpause and see what happens to our creations. There’s an encyclopedia of oscillators, gliders, transistors, memory circuits, self-replicating spaceships, and even modular computers that simulate the Game of Life within itself, all written in a language of cells that live or die according to one extremely simple function of how many of their nearest neighbors are living. Constructs in Conway’s Game of Life are written in a language that transcends our cultures and the physical context of our universe. If we etched a Gosper Glider Gun into a golden record on some future space probe, there’s a decent chance that any alien civilization to recover that record would recognize it as something they’ve already discovered and named, like the Mandelbrot set.

Anyway, trying to read through that encyclopedia of community knowledge made it very clear to me that looking to other rules for cellular automata was not necessary for the pure purpose of finding fresh challenges – the frontier of discovery within the Game of Life is plenty big and plenty accessible, and half a century after its conception, things are only ramping up with more sophisticated programs for accelerating the simulation and searching for patterns.

But I took the option of wondering what else there is, and what even Golly (the most famous and advanced cellular automata tool) doesn’t show me. There’s a reason why cellular automata with float states probably aren’t as much fun to play with – too much chaos with no way to bring it under control. Conway’s Game of Life is often chaotic, but at least with quantization of both cell positions and cell states, everything falls into some assortment of smaller patterns that we can visually identify, give names to, and make generalizations about. Draw any random shape of a dozen live cells in the Game of Life and watch it decompose into moving “gliders” and stationary “stoplights” and “beehives” and other things – none of them will interfere with or destroy another except by the general rules that can describe each of them in a vacuum. Two gliders either collide with each other, or pass by each other with no interaction of any kind. In a world without integer states for cells, I strongly suspect that it is difficult for any machine that can exist in a vacuum to co-exist with a nearby copy of itself or another machine – it might be like trying to fly an airplane in a world with other airplanes, but the wake turbulence travels in all directions at the speed of light, and instead of the turbulence being made of air, it’s made of a torrent of solid airplane parts.

This is a problem affecting most 2-dimensional cellular automata rules. The good rules must be sought out, and Life is one of them. It doesn’t make sense to ask whether Life is self-regulating, and the answer might seem to be no (since one misplaced cell can destroy a creation of any size), but it doesn’t seem to matter because of how any finite area in Life has a finite number of states. The state of an area is the same as the code that controls what it will do, and this is why a glider will glide no matter what goes on around it, as long as those events don’t change the cells inside the bounding area of the glider. In a world with infinite states for any area of any size, two gliders passing each other might destroy each other by default, because infinitesimal effects on each other might push them out of whatever distinct shape of ranges of cell states act glider-like.

Nevertheless, I decided that cellular automata with non-integer states were well worth experimenting with – maybe only because they pack infinitely more information into the same number of calculations, and because I didn’t know what there was to learn – are they good for computing? Is there a rule that’s good for building computing machines out of cells – maybe even more compactly than in Conway’s Game of Life?

Or,

Is there a rule in the form Z -> sin(sum(neighbors of Z)*a)^b which behaves similarly to Conway’s Game of Life? (A rule where large machines can be built from smaller machines, where oscillators and spaceships can exist, and where the appearance of complete chaos is avoided?)

My latest project FloatAutomata.py aims to discover this.

github.com/JohnDorsey/FloatAutomata.git

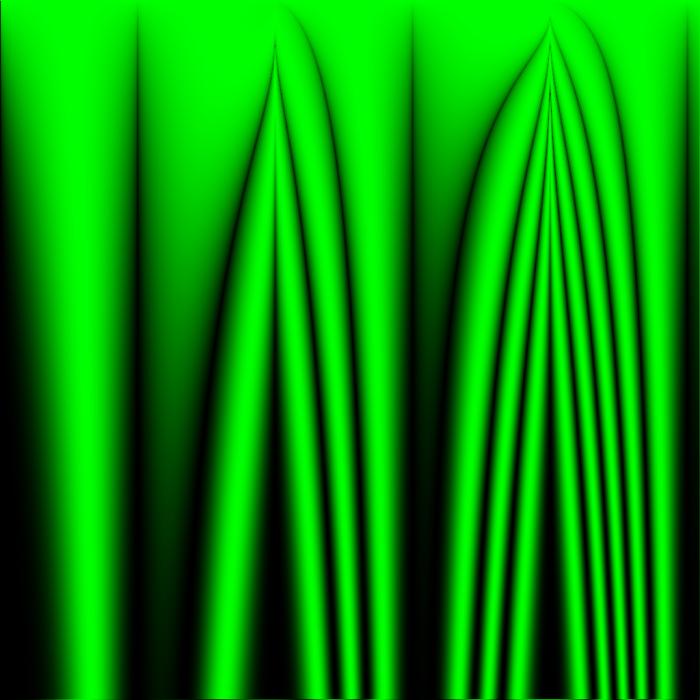

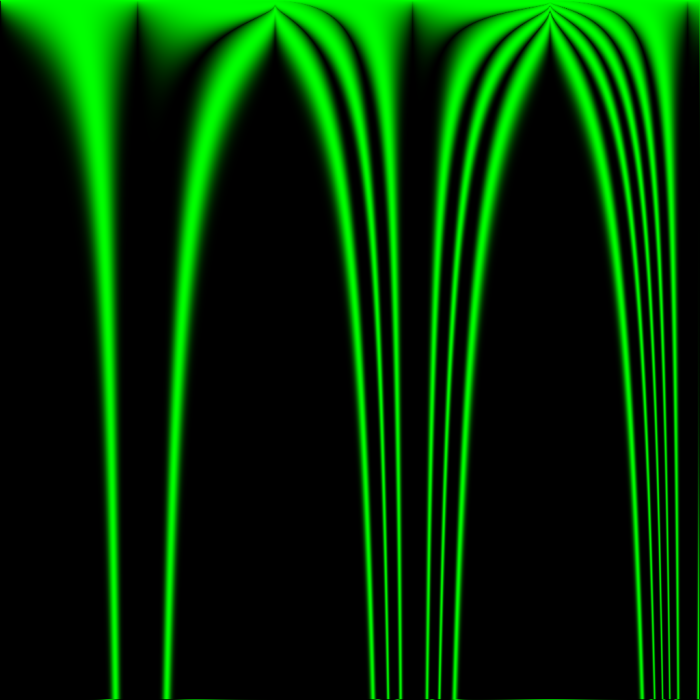

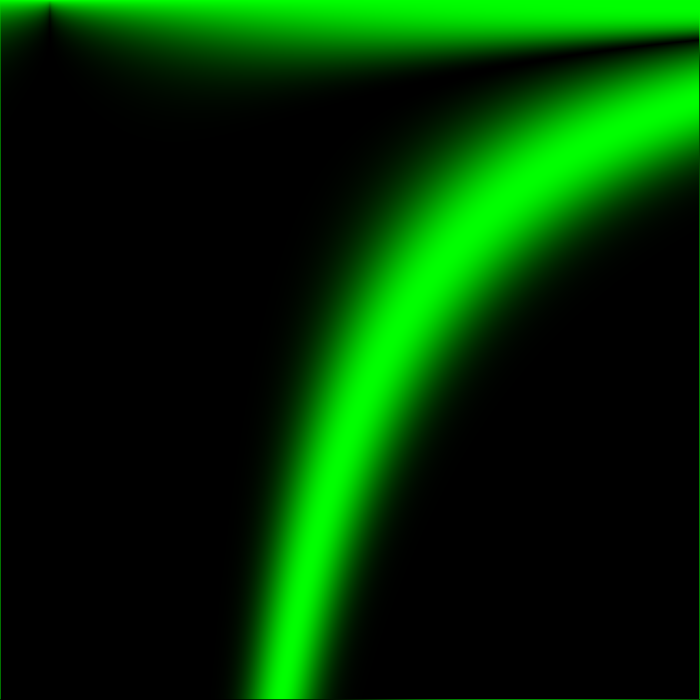

In my recent simulations, I aim to search for ideal rules by testing all rules at once in a shared grid. Each cell’s position determines the parameters of the rule to be used, seen as the variables x and y in the image caption. Although no cell can interact with cells of the same rule, each cell will be interacting with cells of highly similar behavior, hopefully leading to large areas of an image all demonstrating good orderly behavior in areas centered around the pixel with the perfect parameters to create that behavior – just as the Mandelbrot set mimics whatever Julia set is formed by the value C equal to that location, but never perfectly re-creates a Julia set.

Y is measured from the top of the image in pixels, so in these 1024×1024 images, a rule definition which contains (y/512) means that that expression will range from 0 to 2 between the top edge of the image and the bottom edge.

In this entire post, I never resample images – each pixels corresponds to exactly one cell. Every cell state between 0.0 and 1.0 maps to a green channel value between 0 and 255 unless otherwise stated. Every simulation starts with all cells set to 0.5 unless otherwise stated.

The above image of the world at 64 iterations shows that, at least with the way I am choosing to initialize the world, there are no groups of similar rules that all create sparse activity. From images like these, I can’t determine what a only a few live cells would do in a vacuum, because none of them are alone without constant outside interference from other nearly-random cells… Starting with a few live cells is one of the best ways to demonstrate the strengths of Conway’s rule for creating complex organized motion, and this simulation doesn’t do that.

Good rules might be in there, and they just aren’t being given a fair chance at demonstrating order.

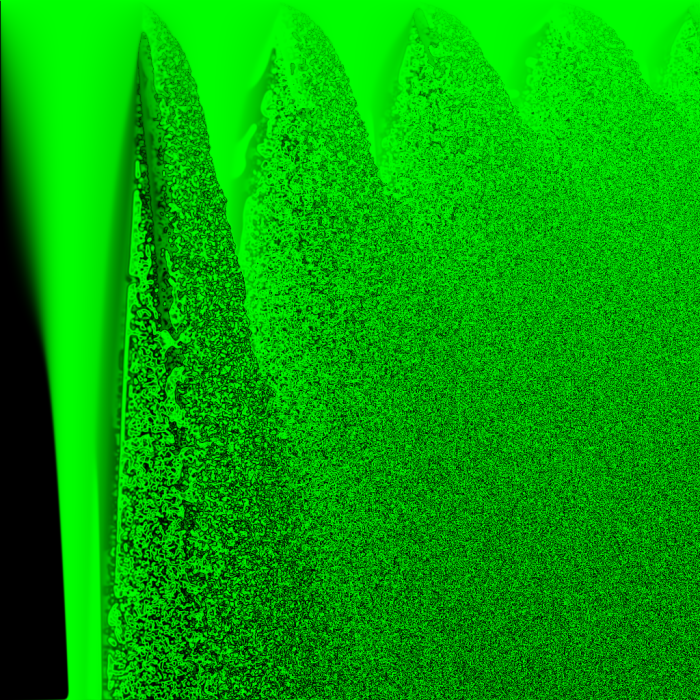

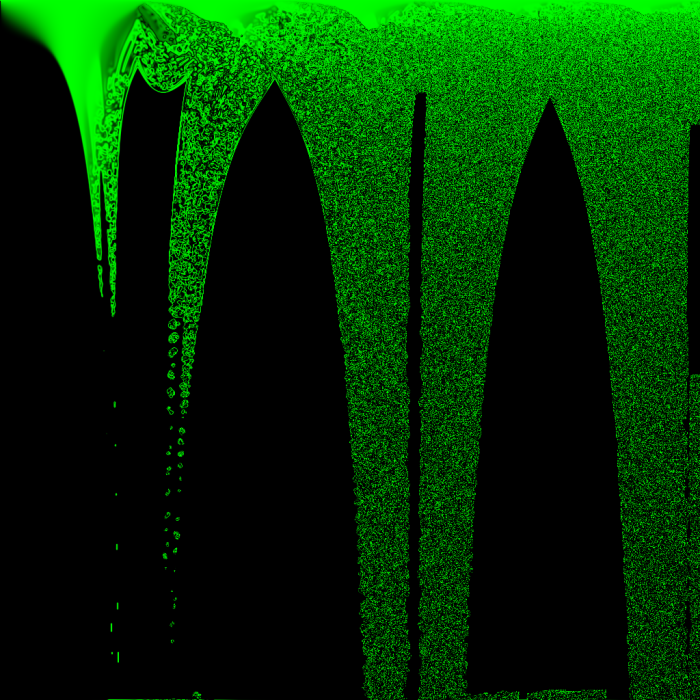

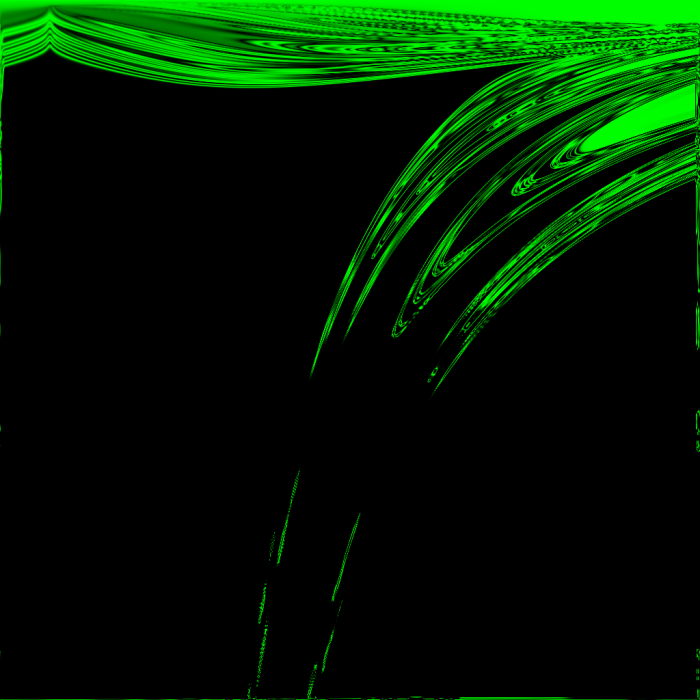

This render is simply the first render zoomed out. Since there’s one cell per pixel, zooming out changes the number of cells in any area within the space of the parameters used for the rule, so zooming out must change the observed behavior of every part of the world. Cells that previously had neighbors with rule parameters different from their own by 1/512 now have neighbors with rule parameters different from their own by 1/64.

I zoomed out this far because I didn’t want to miss an interesting rule, but what I learned from zooming out this far was discouraging…

The noise bleeds like ink until it fills up the whole world.

Generally, in Conway’s Game of Life, endless growth (of live cell population) is something that needs to be designed, not something that happens randomly. I can think of only one situation in which Conway’s Game of Life produces unlimited chaos…

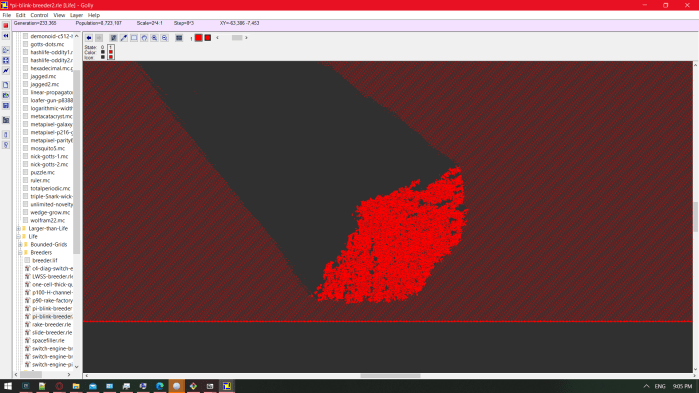

In an experiment I did in Golly, I required an infinite world of repeating gliders, and I used the preset pi-blink-breeder2 under patterns>Life>breeders.

The pattern info includes this attribution:

#C An unusual breeder (quadratic growth) pattern. #C By Jason Summers and David Bell, 6 Sep 2002; from "jslife" archive.

The breeder (a machine that constructs machines that construct gliders) is not important to the experiment – I am only concerned with the area of gliders it produces. In their midst, I drew exactly one glider traveling in the opposite direction, so that it collided with one of them after a while, and this was the result:

That’s essentially a ~200,000-car pileup, which would continue to grow infinitely if it didn’t hit the breeder’s wick of glider builders. In the best-behaved rule that I know of, all it takes to get an infinite chaotic mess is for the world to be initially full (of gliders).

If all I could see of this simulation were a section of the chaos coral, and I were asked whether I thought the rule that created it were Turing-complete, I might say “not really, I mean, you couldn’t practically make a computer out of it like you can with Life” not knowing that I was looking at Life.

I’m saying that none of my experiments so far offer strong evidence that a life-like rule using a sine function either does or doesn’t exist. In future experiments, I should test sine-based rules the same way I test rules by hand in Golly – apply the same rule to the whole world, edit in a handful neighboring live cells in a small random shape that isn’t symmetrical, and hit the play button. In FloatAutomata.py, this would look like quantizing the parameters of rules to make areas of about 64×64 cells that all have exactly the same rule, and not starting the simulation with every cell equal to 0.5. Each square of one rule should start with only a handful of nonzero cells in a cluster near the center.

In the meantime, here are the other experiments I’ve already performed with the whole world starting as 0.5-filled:

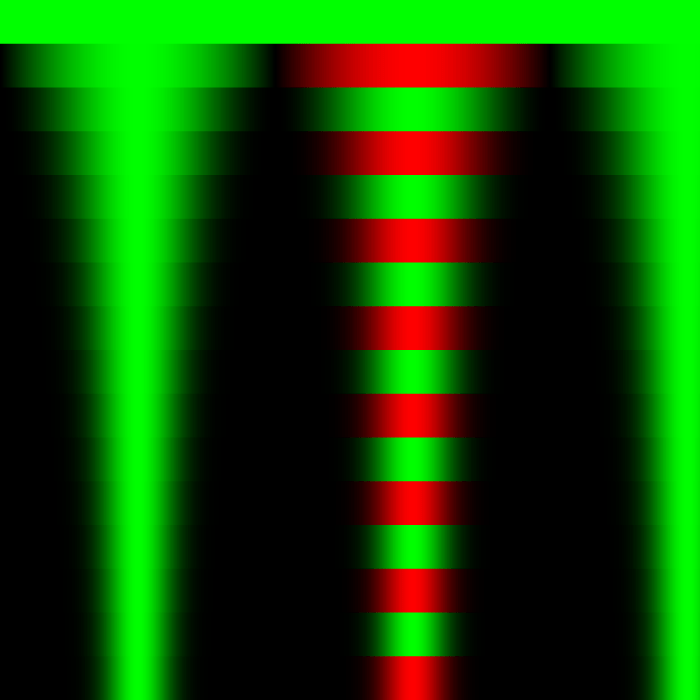

It might seem like the boundary areas between emptiness and noise are good candidates for well-behaved rules, but I think that if this were true, the boundary areas would not constantly be moving!

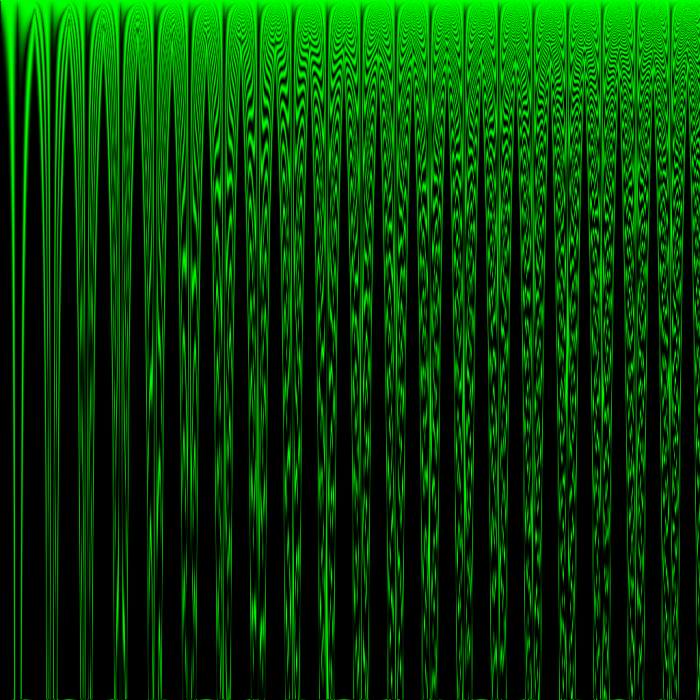

Also note that toroidal wrap was enabled for every one of these experiments, and its effects can sometimes be seen in noise leaking in from the edges of an image to a maximum distance in pixels equal to the number of iterations to happen so far – it’s just because they were exposed to pixels on the opposite edge of the image. It usually doesn’t impact the image at the top or left edges, where one of the parameters is usually zeroed out anyway. For example, in the above image of Z -> abs(sin(sum(neighbors)*x/512))^(y/64) after 16 iterations, the bottom edge of the image has a line of noise caused by exposure to the top edge, but the top edge has no such line of noise.

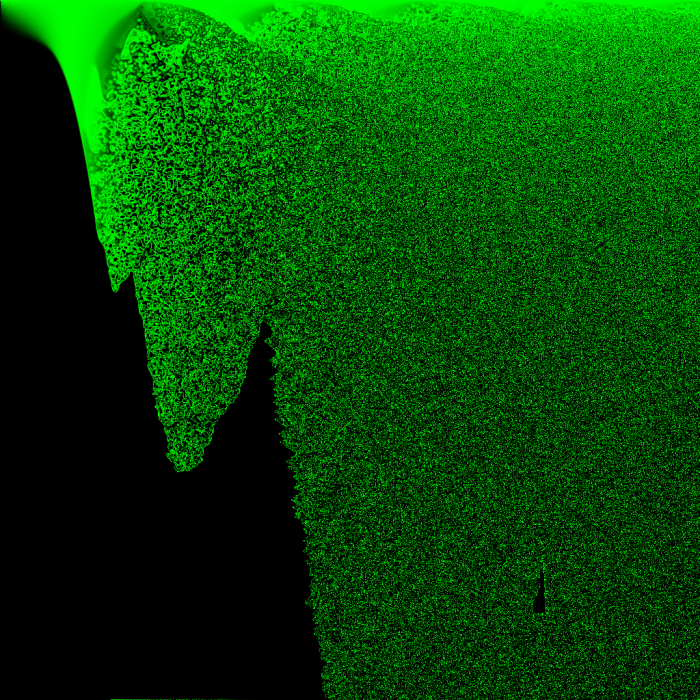

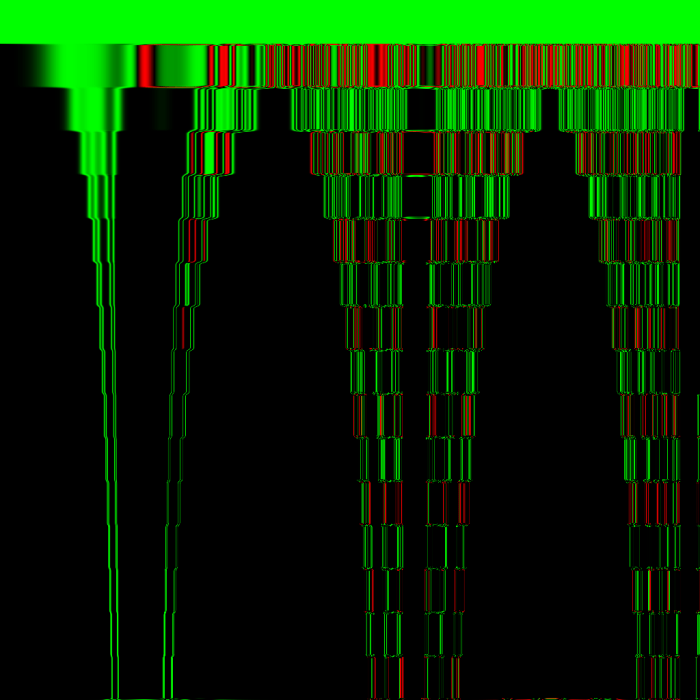

In the above images, anything that looks noisy is located very close to an area that was active in previous iterations – there are no gliders, and all things that look like islands of stability seem to eventually die. Except for two! their coordinates are (429, 720) and (518, 762), giving them the approximate rules:

Z -> abs(sin(sum(neighbors)*0.479736328125))^(11.25) Z -> abs(sin(sum(neighbors)*0.50146484375))^(11.90625)

These will be investigated at a later date.

Even so, the above images serve to demonstrate that which areas of the image appear vital and stable is highly dependent on which areas of the image had ideal starting conditions from the few iterations after the world’s creation, which in turn depends on which rules are good at creating chaos from a starting neighborhood of 8 cells all with the state 0.5.

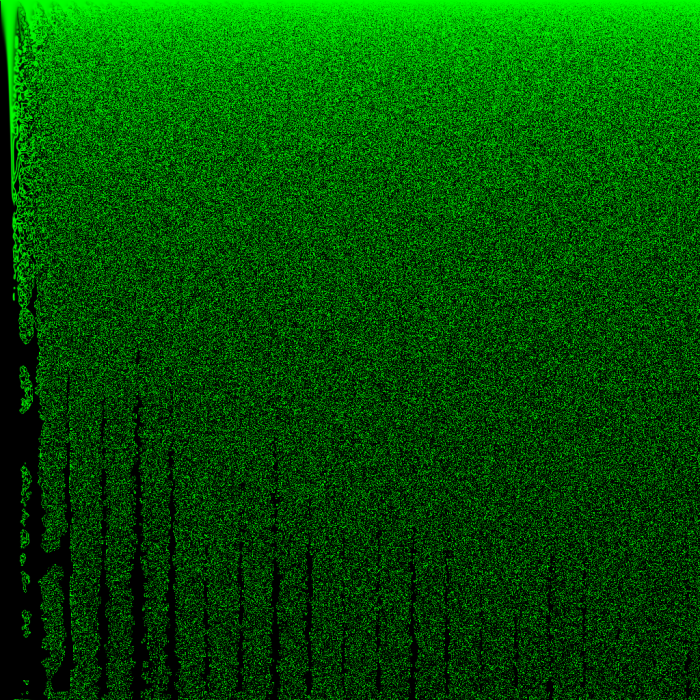

A new color palette has been introduced – reds code for negative values in the same range as greens. Negative numbers are allowed now that exponents are limited to integers – I didn’t want to deal with complex math on my first day of experimenting.

Note in the center left of the image, near the bottom end of the second of the image’s four tornado shapes, there appears to be a symmetrical barcode shape – animated over time, this looks like traveling along a binary tree layer by layer. Conway’s Game of Life never does this, but I believe some other cellular automata with binary states do. Just like what is seen here, those rules produce growing regions of noise at either end of a barcode’s bars until the barcode is consumed by the noise. In this experiment, the barcodes are initially stretched between the boundary lines of integer exponents in the rule (64 pixels per integer value).

I may upload additional experiments of the same type before continuing to testing of individual rules with more fair (non-solid) starting states of the world. I will also cover some surprisingly orderly rules using the tangent function!